We visit with White-winged

Crossbills visiting a "marble orchard" on a glacial

kame in

Wyandot County, Ohio...

White-winged

Crossbills feasting on hemlock seeds, Oak Hill Cemetery,

Wyandot County, Ohio.

Old fashioned cemeteries are great birding spots, and there's something touching about beautiful birds visiting our beloved. Oak Hill Cemetery, located a few miles due south of Upper

Sandusky,

Wyandot County, Ohio is a great example, a wintergreen garden full of mature spruce, hemlock, and arbor vitae. Just find the community of Upper

Sandusky, Ohio, then leave town going south on Route 67 a short distance to county highway 119. Go left on 119 to the first curve and enter at the gate.

Birding begins as you drive along the gravel entry passing a long hedge of tall arbor vitae ("tree of life") watching for Pine

Siskins. Next, head for the nearest magnificent spruce and hemlock trees shading the "marble orchard" (That's areal photo interpreter jargon for old cemeteries, often placed on glacial

kames.

Kames really 'pop' when viewing 3D stereo images for terrain analysis. Cemeteries were often placed on hilly glacial

kames as were orchards--both uses required well-drained soils).

Monday, Jackie and I, with naturalist Kim Banks stopped by Oak Hill Cemetery to glimpse the visiting White-winged

Crossbills reported by Rick Counts and others on the

Ohio Birds listserv this weekend. Rick was there and he commented that he'd been stopping by this cemetery for ten years looking for birds; perseverance pays! Through birder generosity and the

internet, we all net benefit.

We saw a flock of

crossbills as soon as we entered the cemetery, even before we could lower our windows to hear their cheery calls. We followed the flock to a large hemlock where birders already had them staked out. We got the low-down as we approached the observers, Ben Warner was there with Rick. There were about 40 birds total, earlier, including a Red

Crossbill in the morning, and a few Pine

Siskins, too.

We saw at least two flocks of White-winged

Crossbills during our visit. The larger flock of 26 birds included both sexes and cooperated nicely. Red-bellied Woodpeckers were vocal, too. The red-

bellied's are local but the

crossbills are rare visiting nomads moving south to the tune of melodies we can't hear, but we think they are conducted by the northern cone crop cycles and such. This year is shaping up as a good invasion year--watch the

listserv for a sighting near you!

Our most rewarding sighting unfolds like this: First, we hear cheery calls as a noisy flock wheels overhead passing this evergreen and that until they choose a cone-laden tree to visit. They drop in, spreading throughout the treetop and vanishing instantly among the green boughs. Next, we approach the tree and scan. Soon we begin seeing one

crossbill after another high in the tree. Their antics tickle smiles across our faces. There are lots of raspberry males and limey females busily wedging cone scales. They bring to mind little parrots, the way they cling in all manner of positions, bouncing and swaying in the wind, while getting at the cones.

As time passes we see more and more as they descend the outer boughs of the evergreen, lower and lower, until nearly in reach; these guys are tame. Rick comments, "I bet these guys have never seen a human." They are seeing plenty at Oak Hill Cemetery, the word is out.

Ohio's landscape offers interested observers limitless lessons in glacial geology. It's Glacial Geology 101 everywhere you look. Geology is womb to biological diversity, even when humans intervene with evergreens. This cemetery was placed long ago by people who had to dig graves the old fashioned way, by hand. Like many older cemeteries in central Ohio, it's on a steep-sided glacial deposit, a pile of sand and gravel called a

kame.

Kames are ice-contact stratified drift, that's

geo-parlance for water sorted coarse sediments deposited in irregular piles or terraces at the snouts of melting ice sheets.

Cemeteries often sprout on glacial

kames, and grow glossy headstones and tall evergreens thanks to our cultural practices! The

crossbills are attracted by the evergreens we plant, our symbols of everlasting life growing alongside our loved lost, and the birds are fed as we are comforted!

Glacial

kames often grow prairie plants, too, a flora preserved in remnants today only because these cemeteries have unkempt brushy margins. These are search-central for rare plant hounds looking for new records of remnant

prairie flora. Here's a tip, look closely at those hard to mow steep slopes, especially along the margins of those out-of-the-way plastic flower dumps found nearby every cemetery! I'll bet locals named this pretty spot "Oak Hill Cemetery" because it was formerly a bur oak

savannah.

Glacial

kames are nomads moving to a different drummer. Their scale of motion is measured in ten-thousand year intervals, a glacial pace. They are nomads nevertheless. Their rocky mix is carried from the north and left piled until the next ice sheet advance punches its travel ticket for a more southerly location. Ice sheets will came again. Our sins will be erased, and North America will begin again (less a lot of today's species), so

sayeth those pesky geologists.

Bird-Lore, the "official Audubon Societies publication" at the turn of the 19th Century

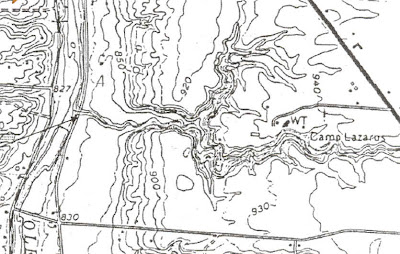

Bird-Lore, the "official Audubon Societies publication" at the turn of the 19th Century Topographic map of Lazarus Run and Deer Run, Delaware County, Ohio. Lazarus Run courses east-west. Deer Run joins from the north. The Olentangy River at far left.

Topographic map of Lazarus Run and Deer Run, Delaware County, Ohio. Lazarus Run courses east-west. Deer Run joins from the north. The Olentangy River at far left.